To support or to deny: mentoring or gatekeeping?

I think a lot about mentoring — both the common ways we mentor in scientific environments and the ways we should be mentoring based on a wealth of evidence about good practices for supporting individuals from a broad range of backgrounds.

Mentoring can be advising on specific goals or warning what to avoid on the path to success. Whereas it can be critical to weigh the merits of a particular opportunity, too frequently mentors outright advise against a particular path because it doesn’t fit their own experience or tradition. Such viewpoints can result in rather than mentoring.

I’ve reflected on my own engagement in mentoring scholarship and leadership development even though a mentor advised me that it could distract me from my “real” research. I’ve found this work highly rewarding, and based on the work and conversations it has stimulated, it meets a need in the scientific community.

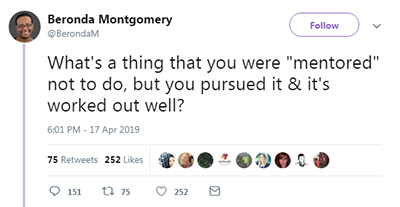

This personal reflection piqued my interest in hearing from others about their successes after ignoring mentors’ advice. I don’t know what I expected in response when I tweeted a question about things that people have been mentored to avoid but pursued anyway.

The responses were both heart-wrenching and encouraging. I was encouraged by the individual successes and, when I reflected on the collective responses, by the lessons that emerged on how we can be more effective, responsive mentors.

Major themes materialized, including research priorities, trajectories and professional outlook; family planning issues; public engagement and communication; identity-related issues; and tone policing (criticizing someone for expressing emotion).

Research priorities

The respondents told me they were discouraged around issues that could be generalized as research framing and trajectory. They said mentors advised them which areas of research were worth pursuing and which were not based on what was popular or fundable or likely to be successful or have a high impact. This extended to mentoring against broad research interests and in favor of a narrow research focus so they could become an identified expert on a particular topic. One respondent expressed the common sentiment, “I was mentored to focus on a single research track.”

Publishing advice focused on traditional priorities: publish in high-impact journals and venues and ignore trends toward open access and preprints. One person specifically mentioned being “mentored … not to shun … paywalled journals as a new assistant professor.”

Respondents said they were advised not to seek positions outside of research-intensive or R1 institutions — that is, they should avoid work in high schools, community colleges, primarily teaching/undergraduate institutions or liberal arts colleges, and historically black colleges and universities or minority-serving institutions. One who was advised not to take a tenure-track job at a community college wrote, “I was told if I did that, I’d never get to go back to a 4 year school.”

Some were told not to apply for prestigious awards because a previous applicant deemed competitive had not received the honor. This advice often was framed as wanting to help mentees not waste their time in an unsuccessful pursuit. Numerous or marginalized individuals said their mentors advised them not to pursue advanced education, valued positions or prestigious opportunities because the mentors were concerned about their potential for success.

Family and career

Advice about when or whether to have children while pursuing an advanced degree or a milestone such as tenure — nearly exclusively directed at women — was surprisingly frequent. For example, one respondent wrote, “I was told in grad school that to succeed as a woman in science I should not get married or have kids.”

This advice extended to taking time off for family or other nonacademic pursuits, and generally the advice was to avoid career-derailing or -ending activities rather than proactive suggestions on how to navigate such a path successfully.

Many respondents said they got specific advice about what to avoid in career pathway decisions. Mentors advised them not to serve in disciplinary societies or engage in editorial service before receiving tenure or promotion. They also warned against pursuit of administrative positions. Some may argue that this is good mentoring advice, but mentees asking about such opportunities want guidance on navigating a path of interest — not wholesale advice to avoid it. Mentors often warned against getting distracted by causes or commitments to specific service activities, rather than discussing . Conversely, some scholars of color or other marginalized individuals were advised to pursue such activities even to the detriment of advancing their scholarly research goals.

Engagement and identity

Most mentors did not see value in engaging with the public, news outlets or other outreach venues — especially through a social justice lens. Mentees were urged to avoid the use of social media or public interfaces such as blogging for science communication, which many mentors saw as a distraction. One respondent recalled being told, “Don’t waste time communicating your science to and engaging with people outside of the science community.”

In a couple of instances mentioned above, mentors seemed to give distinct advice to individuals from marginalized groups. Mentor support was lacking in other areas associated with issues of identity. Individuals from underrepresented groups were encouraged not to conduct research on racial, ethnic, gender or other identity groups of origin or affinity. They often were advised not to speak freely and were subject to tone policing, including advice to avoid both real and perceived politics.

From what to why

As a mentor, have you offered advice in the aforementioned areas? Do your mentoring responses seem to match those described as advice that people went against — and for which that breaking away worked well?

Stop and think deeply about your intentions when you provided the advice or mentoring in question. If you can’t justify your intentions in ways that are not about self-affirmation or imprinting, reconsider your advice in the moment and your mentoring philosophy and approaches more generally. Also, stop and assess whether the identity of the person you are mentoring alters your advice.

One way to adapt mentoring to the needs of a specific mentee is to move away from offering “what” advice to offering an effective “why.” Frequently, advice given by mentors centers on “what”; you might tell a student to write daily, but writing every day doesn’t work for everyone. As one respondent wrote, “I was told to schedule my writing. I can’t write on a schedule.”

Rather, the more helpful advice is to find the groove, pace or frequency that leads to writing regularly and productively.

Those who insist on a very specific “what” often are maintaining norms or gatekeeping. Lisa Parker, senior director of alumni engagement at Michigan State, wrote on Twitter, “There are two types of mentors — those who help establish/maintain norms and those who help disrupt them.”

The advice shared with me on Twitter was based mostly on mentors’ understanding of accepted norms, sometimes under the guise of offering advice that is best for you or . These mentors yielded to the common approach of status quo gatekeeping rather than embracing an opportunity or supporting individuals on their personally defined paths and .

I long for the day when mentors focus deeply on supporting the goals of mentees based on imagining the institutions and communities we can be when people pursue their goals and motivations with progressive mentoring support rather than keeping the gates to reaffirm the choices and identities of those that have come before.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition weekly.

Learn moreFeatured jobs

from the

Get the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Careers

Careers highlights or most popular articles

Upcoming opportunities

Just added: Register for ASBMB's virtual session on thriving in challenging academic or work environments.

Who decides when a grad student graduates?

Ph.D. programs often don’t have a set timeline. Students continue with their research until their thesis is done, which is where variability comes into play.

Upcoming opportunities

Submit an abstract for ASBMB's meeting on ferroptosis!

Join the pioneers of ferroptosis at cell death conference

Meet Brent Stockwell, Xuejun Jiang and Jin Ye — the co-chairs of the ASBMB’s 2025 meeting on metabolic cross talk and biochemical homeostasis research.

A brief history of the performance review

Performance reviews are a widely accepted practice across all industries — including pharma and biotech. Where did the practice come from, and why do companies continue to require them?

Upcoming opportunities

Save the date for ASBMB's in-person conferences on gene expression and O-GlcNAcylation in health and disease.