Proteins and lipids вҖ” a complicated relationship?

Researchers have been discussing for many years the role of the lipid matrix in regulating the activity and the organization of membrane proteins. A variety of effects have been singled out and studied qualitatively and quantitatively in model systems. However, the applicability of those results to living cells is — in many cases — unsatisfactory. Here, we would like to make the point that the complexity of the lipid–protein matrix in cells alters the physico-chemical mechanisms of protein–lipid interactions to an unknown extent when compared to model systems.

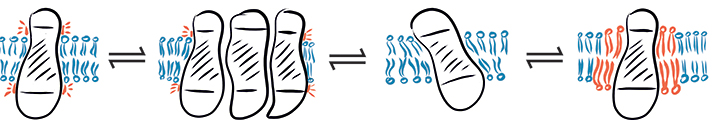

In a complex environment, hydrophobic mismatch may cause a protein to fluctuate between different states: (from left to right) hydrophobic mismatch, protein aggregation, protein tilting and recruitment of long-chain lipids.SCHEMATIC PROVIDED BY EVA SEVCSIK AND GERHARD J . SCHГңTZ

In a complex environment, hydrophobic mismatch may cause a protein to fluctuate between different states: (from left to right) hydrophobic mismatch, protein aggregation, protein tilting and recruitment of long-chain lipids.SCHEMATIC PROVIDED BY EVA SEVCSIK AND GERHARD J . SCHГңTZ

We shall discriminate between global and local mechanisms. Global mechanisms are mediated by lipid-bilayer properties; local mechanisms denote a direct molecular interaction between a protein and a lipid molecule. Examples of global effects include curvature, hydrophobic mismatch and preferential partitioning in phase-separated membranes (“rafts”) (1–3); examples of local mechanisms are the direct binding of cholesterol to CRAC domains (4) or of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate to protein subunits (5).

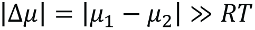

Formally, we may characterize a protein via its chemical potential µ, with the values for two different functional or structural states, µ1 and µ2. If  (R is the gas constant, T the temperature), a pronounced preference for one of the two states will occur. In contrast, for

(R is the gas constant, T the temperature), a pronounced preference for one of the two states will occur. In contrast, for  , we expect no preferred state.

, we expect no preferred state.

Most of the data for global mechanisms come from studies on simple, well-defined model systems, which allow for specifically addressing individual parameters. To emphasize the effects, such model systems usually are selected to achieve substantial contrast between µ1 and µ2. Examples would be the partitioning of proteins into ordered versus disordered phases in phase-separated lipid bilayers (6) or the recruitment of proteins to lipid vesicles with different curvature (7). Also, for local mechanisms, chemical potentials are the appropriate means of quantitating a protein’s state: µ1 denotes the lipid-bound state, µ2 the unbound state, and  the equilibrium binding constant.

the equilibrium binding constant.

In cell membranes, however, a plethora of lipid species with varying properties, such as different head groups, acyl chain lengths and degrees of saturation, increases the complexity of the situation. The consequence for global mechanisms will be myriad chemical potentials describing the possible states of the protein, which can be approximated by a continuous energy landscape: Proteins essentially fluctuate between the different states. In some cases, cells may amplify the difference in chemical potential by de novo assembly of membrane structures, such as clathrin-coated pits, so that the partitioning or activity contrast will become more pronounced.

Also, in the case of local mechanisms, a variety of lipids may be able to interact with the protein of interest, potentially with only slightly different affinities. This leads to the recruitment of specific lipid species to the vicinity of the protein and an essentially continuous distribution of chemical potentials. Again, in some cases, preferred interactions of the protein with one type of lipid occur, yielding additional discrete values of µ.

What would be the consequences of a continuous distribution of chemical potentials? There would be no clear-cut states of a protein. For example, hydrophobic mismatch, on a stochastic basis, may lead transiently to demixing of the protein, the recruitment of a shell of long-chain lipids and membrane curvature. The system would fluctuate between these scenarios. Only in cases where the energy continuum splits up, or where distinct extra-states exist, can we expect distinct states of a protein. In conclusion, studies of well-defined model systems certainly help our understanding of fundamental physico-chemical properties, but the complexity of the live cell environment provides many more options to minimize the global energy of the system.

References

- Milovanovic, D. et al. Nat. Commun.6, 5984 (2015).

- McMahon, H.T. & Boucrot, E. J. Cell. Sci.128, 1065 – 1070 (2015).

- Van Meer, G. et al. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol.9, 112 – 124 (2008).

- Fantini, J. & Barrantes, F.J., Front. Physiol.4, 31 (2013).

- Hamilton, P.J. et al. Nat. Chem. Biol.10, 582 – 589 (2014).

- Dietrich, C. et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA98, 10642 – 10647 (2001).

- Hatzakis, N.S. et al. Nat. Chem. Biol.5, 835 – 841 (2009).

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition weekly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and weвҖҷll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Transforming learning through innovation and collaboration

Neena Grover will receive the William C. Rose Award for Exemplary Contributions to Education at the 2025 ASBMB Annual Meeting, April 12вҖ“15 in Chicago.

Guiding grocery carts to shape healthy habits

Robert вҖңNateвҖқ Helsley will receive the Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator in Lipid Research Award at the 2025 ASBMB Annual Meeting, April 12вҖ“15 in Chicago.

Quantifying how proteins in microbe and host interact

вҖңTo develop better vaccines, we need new methods and a better understanding of the antibody responses that develop in immune individuals,вҖқ author Johan Malmström said.

Leading the charge for gender equity

Nicole Woitowich will receive the ASBMB Emerging Leadership Award at the 2025 ASBMB Annual meeting, April 12вҖ“15 in Chicago.

CRISPR gene editing: Moving closer to home

With the first medical therapy approved, thereвҖҷs a lot going on in the genome editing field, including the discovery of CRISPR-like DNA-snippers called Fanzors in an odd menagerie of eukaryotic critters.

Finding a missing piece for neurodegenerative disease research

Ursula Jakob and a team at the University of Michigan have found that the molecule polyphosphate could be what scientists call the вҖңmystery densityвҖқ inside fibrils associated with AlzheimerвҖҷs, ParkinsonвҖҷs and related conditions.