WhatтАЩs in your dimer?

The term “homodimer” — shorthand for “sequence homodimer” — connotes a protein molecule composed of two monomers with identical primary structures. It often is assumed these proteins function as pairs of independently operating monomers, but there are other scenarios. Many homodimers show a substrate or cofactor binding with high affinity to only half of the seemingly available sites and behave as . This permits allosteric regulation that is not possible with true conformational homodimers.

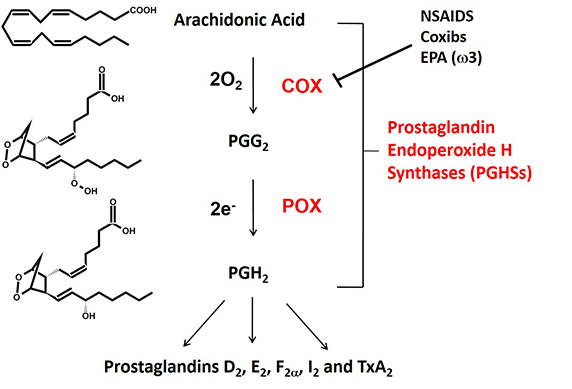

Fig. 1. The cyclooxygenase (COX) and peroxidase (POX) reactions catalyzed by prostaglandin endoperoxide H synthases (PGHSs). There are two isoforms that are commonly known as cyclooxygenases-1 and -2 (COX-1 and COX-2).

Fig. 1. The cyclooxygenase (COX) and peroxidase (POX) reactions catalyzed by prostaglandin endoperoxide H synthases (PGHSs). There are two isoforms that are commonly known as cyclooxygenases-1 and -2 (COX-1 and COX-2).

Prostaglandin endoperoxide H synthases are homodimers that function as conformational heterodimers. These enzymes, commonly known as cyclooxygenases, or COXs for short, catalyze the committed step in prostaglandin synthesis — the conversion of arachidonic acid to (Fig. 1). There is a constitutive COX-1 and an inducible COX-2. These enzymes are composed of catalytic (Ecat) and allosteric (Eallo) monomers (Fig. 2). With COX-2 at least, Ecat and Eallo each remain fixed in the same form during the . Ecat binds heme more avidly than Eallo, and as originally observed by Richard J. Kulmacz and coworkers, maximal COX activity requires only one heme per dimer (See and ).

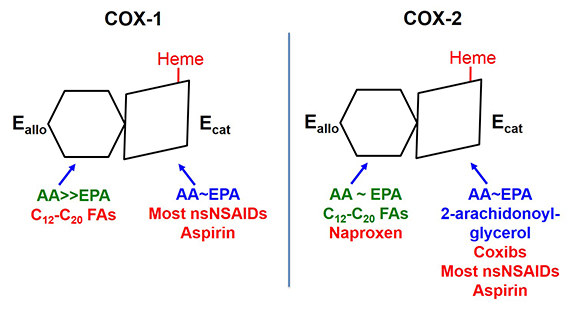

COXs are regulated by fatty acid tone — the cellular composition and concentration of free fatty acids. Different free fatty acids bind with different affinities to Ecat and Eallo (See and ). Free fatty acids binding to Eallo regulates the catalytic efficiency of Ecat. In general, the most common free fatty acids including palmitate and stearate and oleate inhibit COX-1. In contrast, palmitate is relatively specific for stimulating COX-2. Overall, high ratios of common free fatty acids to arachidonic acid, and low concentrations of arachidonic acid, activate COX-2 while suppressing COX-1. COX-1 and COX-2 are also differently affected by the omega-3 fish oil free fatty acids. For example, eicosapentaenoic acid inhibits COX-1 but not . The molecular basis for the differences in these free fatty acids effects remain to be resolved.

The two COX isoforms are sequence homodimers that function as conformational heterodimers. Both enzymes appear as structurally symmetric homodimers in crystal structures but function in solution as conformational heterodimers composed of an allosteric (Eallo) and a catalytic (Ecat) subunit. The subunits of COX-1 and COX-2 differ in their affinities for ligands and in their responses to ligands. Substrates are in blue. Ligands shown in green stimulate COX activity, and those shown in red inhibit activity

The two COX isoforms are sequence homodimers that function as conformational heterodimers. Both enzymes appear as structurally symmetric homodimers in crystal structures but function in solution as conformational heterodimers composed of an allosteric (Eallo) and a catalytic (Ecat) subunit. The subunits of COX-1 and COX-2 differ in their affinities for ligands and in their responses to ligands. Substrates are in blue. Ligands shown in green stimulate COX activity, and those shown in red inhibit activity

Interest in COXs as drug targets highlights their importance. For example, low-dose aspirin targets platelet COX-1 (See and ). Aspirin, naproxen (ALEVE®), and ibuprofen (Motrin®) are mixed COX-1 and COX-2 inhibitors called nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, which relieve pain by targeting COX-2. Celecoxib (Celebrex®) is a coxib – an NSAID more specific for . Mechanistically, most NSAIDs and coxibs bind more tightly to Ecat than Eallo. Naproxen is unusual in being a direct competitive inhibitor of COX-1, but an allosteric inhibitor of COX-2 (See and ). As a consequence, naproxen can inhibit 100 percent of COX-1 activity but only 70 percent of COX-2 activity. This may explain why naproxen has limited adverse cardiovascular side effects compared with .

There is much more to be learned about these COXs including identification of likely dietary influences on these enzymes. Additionally, differences in cellular fatty acid tone may well contribute to adverse effects of COX inhibitors, thereby impacting therapies. Understanding the structure, chemistry and regulation of these enzymes remains an exciting area of investigation.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition weekly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and weтАЩll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Transforming learning through innovation and collaboration

Neena Grover will receive the William C. Rose Award for Exemplary Contributions to Education at the 2025 ASBMB Annual Meeting, April 12тАУ15 in Chicago.

Guiding grocery carts to shape healthy habits

Robert тАЬNateтАЭ Helsley will receive the Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator in Lipid Research Award at the 2025 ASBMB Annual Meeting, April 12тАУ15 in Chicago.

Quantifying how proteins in microbe and host interact

тАЬTo develop better vaccines, we need new methods and a better understanding of the antibody responses that develop in immune individuals,тАЭ author Johan Malmström said.

Leading the charge for gender equity

Nicole Woitowich will receive the ASBMB Emerging Leadership Award at the 2025 ASBMB Annual meeting, April 12тАУ15 in Chicago.

CRISPR gene editing: Moving closer to home

With the first medical therapy approved, thereтАЩs a lot going on in the genome editing field, including the discovery of CRISPR-like DNA-snippers called Fanzors in an odd menagerie of eukaryotic critters.

Finding a missing piece for neurodegenerative disease research

Ursula Jakob and a team at the University of Michigan have found that the molecule polyphosphate could be what scientists call the тАЬmystery densityтАЭ inside fibrils associated with AlzheimerтАЩs, ParkinsonтАЩs and related conditions.