Vital fluids

You never know what you’ll turn out to have in common with your co-workers; science writer John Arnst and I bonded over selling our blood plasma.

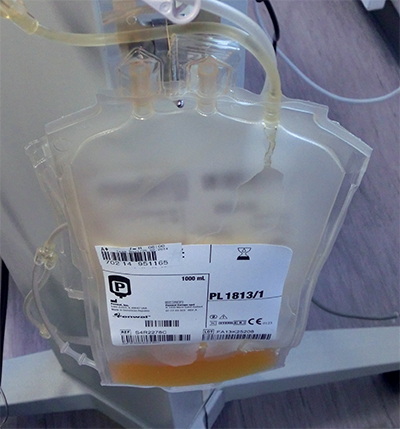

Plasma, the yellowish fluid in which blood cells and platelets are suspended, is essential for treating trauma patients and those with a number of other medical conditions. It’s needed in such large quantities that people get paid for it — though you aren’t technically being paid for the fluid; you’re being compensated for the hour or so that you spend lying in a padded lounge chair with a big needle stuck in one arm. A healthy person can donate about three cups of plasma twice a week. When I did it, my time was worth .

ANKAWأœ/Wikimedia Commons

ANKAWأœ/Wikimedia Commons

In that hour, a whirling machine separates the plasma from everything else in a process called apheresis and returns the blood cells and platelets to your arm. The machine is mostly clear plastic tubes and cylinders, so you can watch the process, which repeats about six times per donation, and monitor the slow drip of plasma into a plastic bottle. When it’s over, a pint of saline gets pushed into your arm to restore the fluid level.

Unlike blood donation, selling plasma is not an altruistic activity. It’s about the dollars on a debit card. John said he did it for about six weeks right after he graduated from college. I was an underpaid newspaper editor and single mom when I sold my plasma off and on for about a year, long enough for my arms to develop some suspicious marks and for my iron levels to dip perilously a couple of times.

While reclining in that lounge chair, I thought a fair amount about the marketing of bodily fluids, so when John mentioned Stephen Withers’ efforts to turn other blood types into O and its possible impact on the blood donation industry, all my old questions came back: Why do people get paid to donate plasma but not blood? If people give their blood for free, why does it cost so much when you get a transfusion? How do blood banks persuade enough people with the right types of blood to donate?

I was not the first person to think about this. Just Google “selling blood” and numerous on the topic pop up.

John writes that the blood industry is in trouble. Can it be saved by science? We don’t have an answer to that question, but our February feature story certainly lays out the issues and explains how blood (both industry and science) got where it is today. It’s a good read.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition weekly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Opinions

Opinions highlights or most popular articles

Who decides when a grad student graduates?

Ph.D. programs often don’t have a set timeline. Students continue with their research until their thesis is done, which is where variability comes into play.

Redefining â€کwhat’s possible’ at the annual meeting

The ASBMB Annual Meeting is “a high-impact event — a worthwhile investment for all who are dedicated to advancing the field of biochemistry and molecular biology and their careers.â€

حµإؤحµ؟ْ impressions of water as cuneiform cascade*

Inspired by "the most elegant depiction of H2O’s colligative features," Thomas Gorrell created a seven-tiered visual cascade of Sumerian characters beginning with the ancient sign for water.

Water rescues the enzyme

“Sometimes you must bend the rules to get what you want.†In the case of using water in the purification of calpain-2, it was worth the risk.

â€کWe’re thankful for our reviewers’

Meet some of the scientists who review manuscripts for the Journal of Biological Chemistry, Journal of Lipid Research and حµإؤحµ؟ْ & Cellular Proteomics.

Water takes center stage

Danielle Guarracino remembers the role water played at two moments in her life, one doing scary experiments and one facing a health scare.