A quantum leap

Film director Mark Levinson often gets asked for advice from people looking to break into the movie-making business. “I tell them, ‘The good news is I didn’t go to film school. The bad news is I got a Ph.D. in physics,’” he says with a laugh.

Mark Levinson Image courtesy of PF Productions

Mark Levinson Image courtesy of PF Productions

While Levinson’s atypical career path is probably not the ideal template for aspiring filmmakers, it is illustrative of his perspective about the unexpected overlap between science and cinema. The “creative impulse is very similar,” he points out. “I think (that similarity) underlines my whole transition.”

Levinson the scientist started out in an M.D./Ph.D. program at Brown University before a professor turned him onto theoretical physics. Even though his passion for science led him to pursue a graduate physics degree at the University of California, Berkeley, Levinson admits that his interests tended to go beyond academia. “I was fascinated by art and artists and how they interacted with society and what their role was,” he says.

A fan of classic movies like “” and “,” Levinson was nonetheless unaware that he could work in the film industry until he was introduced to the films of European directors Lina Wertm├╝ller and Rainer Werner Fassbinder. Observing their distinctive styles helped Levinson become “very conscious of directors.”

Becoming more and more enamored with the idea of working in the film industry, Levinson did what seemingly every Hollywood hopeful does: “I started writing a script,” he says. But even then, Levinson didn’t feel like his career had really made much of a change. “I went from being a graduate student in theoretical physics, where I was sitting in a room, by myself, scratching on pencil and paper, not making money,” he remembers. “And then I was writing a script, and I was sitting in a room, by myself, not making much money and scratching on pencil and paper.” Yet the bigger challenge for Levinson was trying to live with the feeling that he had disappointed his graduate adviser. “It was probably the hardest part,” he admits.

When Levinson first entered the film industry, he scuttled through a series of jobs in various departments until he finally ended up in the editing room. While working there in 1987, he got to meet the acclaimed film editor , who already had won an Academy Award for his work on “.” Surprisingly, Levinson’s scientific training was the catalyst for his meeting with Murch.

“I was an apprentice editor in the same building where he was editing ‘,’” recalls Levinson. “He heard that there was somebody in the building with a Ph.D. in physics, so he sent his assistant down to ask me if I’d go to lunch with him and talk to him about string theory.” Levinson went on to work with Murch on “” (which fetched Murch his second Oscar), “” and “.”

Despite becoming fully immersed in the glamorous world of Hollywood, Levinson always was tempted to use the opportunities afforded by the movie industry to showcase science. “I had never really seen a film that I thought accurately depicted how science really works,” he says. Levinson’s worlds finally collided with the 2013 release of “,” a documentary he directed that follows researchers at the European Council for Nuclear Research in their quest to detect the Higgs boson using the Large Hadron Collider.

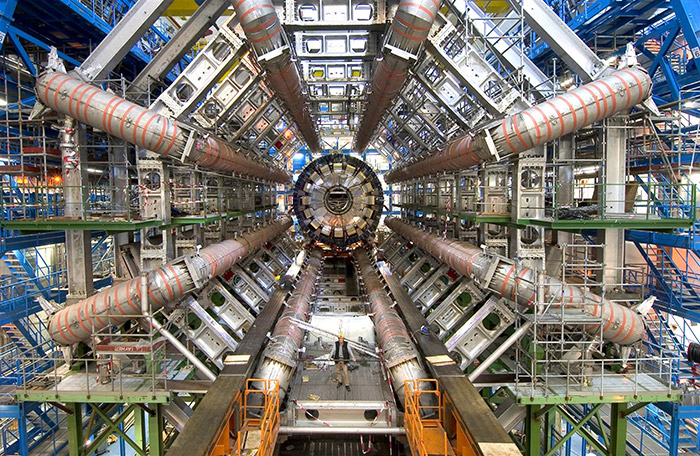

Full view of the open ATLAS DetectorImage courtesy of CERN

Full view of the open ATLAS DetectorImage courtesy of CERN

Rather than follow a standard documentary formula of telling a story through a single pair of eyes, the movie instead relies on six scientists to show the scientific process at work, thereby bringing a human side to research. “We needed to choose people that could bring out the various elements” of the experience, explains Levinson, pointing out that the film’s protagonists range from a fresh-faced postdoctoral fellow to a senior administrator at CERN. “The focus for me always was ‘How are we going to tell a good dramatic story?’” says Levinson.

“Particle Fever” was met with overwhelmingly positive reviews and numerous accolades, including the Audience Award at the 2013 and both the Grand Jury and Brainstorm Prizes at the 2013 . It also enabled Levinson to resolve any lingering guilt about his decision to abandon scientific research all those years ago: One of his most gratifying moments with “Particle Fever” was the positive reception it got from his graduate school adviser. “I feel like maybe I wasn’t a complete disappointment to him in the end,” Levinson says. “‘Particle Fever’ is my gift back to the physics community.”

The success of “Particle Fever” motivated Levinson to continue exploring the overlap between his two passions of art and science. He is working on a film adaptation of Richard Powers’ novel “The Gold Bug Variations.” Titled in reference to Johann Sebastian Bach’s famous work called the “Goldberg Variations” and the Edgar Allan Poe short story “The Gold-Bug,” the novel tells of a young molecular biologist working on the genetic code in the 1950s who derails his scientific career in pursuit of love and music.

CERN's Globe of Science and Innovation at nightPhoto courtesy of PF Productions

CERN's Globe of Science and Innovation at nightPhoto courtesy of PF Productions

From his vantage point, Levinson sees science and cinema as two endeavors where “man is trying to find a representation of the world around him to understand it in some deeper way.” Indeed, in making “Particle Fever,” Levinson says, his interest in the overlap between science and art has reenergized his own belief in the importance of both realms: “These are the things that make us human,” he says.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition weekly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and weŌĆÖll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in People

People highlights or most popular articles

Guiding grocery carts to shape healthy habits

Robert ŌĆ£NateŌĆØ Helsley will receive the Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator in Lipid Research Award at the 2025 ASBMB Annual Meeting, April 12ŌĆō15 in Chicago.

Leading the charge for gender equity

Nicole Woitowich will receive the ASBMB Emerging Leadership Award at the 2025 ASBMB Annual meeting, April 12ŌĆō15 in Chicago.

Honors for de la Fuente, Mittag and De La Cruz

César de la Fuente receives the American Society of MicrobiologyŌĆÖs Award for Early Career Basic Research. Tanja Mittag and Enrique M. De La Cruz are named fellows by the Biophysical Society.

In memoriam: Horst Schulz

He was a professor emeritus at City College of New York and at the CUNY Graduate Center in Manhattan whose work concentrated on increasing our understanding of mitochondrial fatty acid metabolism and an ASBMB member since 1971.

Computational and biophysical approaches to disordered proteins

Rohit Pappu will receive the 2025 DeLano Award for Computational Biosciences at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, April 12-15 in Chicago.

Join the pioneers of ferroptosis at cell death conference

Meet Brent Stockwell, Xuejun Jiang and Jin Ye ŌĆö the co-chairs of the ASBMBŌĆÖs 2025 meeting on metabolic cross talk and biochemical homeostasis research.