Addressing the tangled roots of health disparities

In the United States, black babies at more than twice the rate of white babies.

As adults, black men and women die from and at higher rates than Americans of other races and ethnicities.

While advances in breast cancer screening and treatments have reduced the death rate for all women in the U.S., the death rate has decreased than for white women, resulting in a significant disparity. For example, from 1999 to 2013, the most recent period for which there are data, black women in Houston were 72 percent more likely to die from breast cancer than white women.

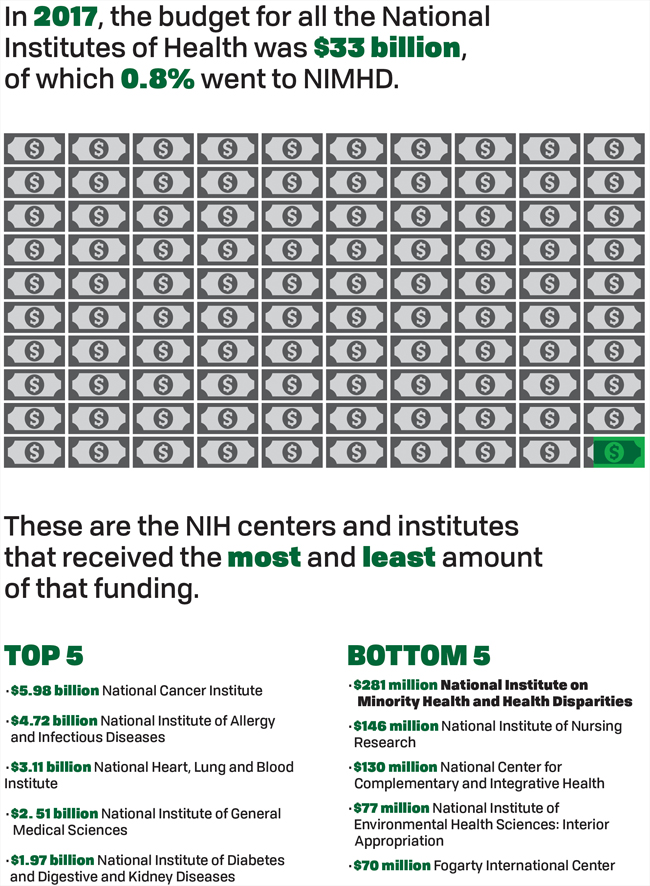

The study of health disparities, which includes any condition disproportionately affecting one racial, ethnic or gender group, is a burgeoning, relatively young research field. The National Institutes of Health established the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities in just 2000 and then redesignated it as the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities in 2010 as part of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act.

A product primarily of poverty and unequal access to health care, health disparities are a staggering challenge. The problem is as entrenched as the wealth gap — due to the strong correlation of income and life expectancy in the U.S., the richest 1 percent of American women and men live an average of years longer, respectively, than the poorest 1 percent.

Clayton Yates has been a faculty member at Tuskegee University for 11 years.COURTESY OF CHRISTOPHER RENEGAR

Clayton Yates has been a faculty member at Tuskegee University for 11 years.COURTESY OF CHRISTOPHER RENEGAR

However, the problem goes deeper than income. The chronic stress caused by economic insecurity, discrimination and systematic racism is understood to have negative effects on the health of millions. Additionally, a growing body of evidence suggests the cellular stress caused by systemic trauma can have epigenetic-based detriments to the health of future generations. For a small number of diseases — including prostate cancer, triple-negative breast cancer and pre-eclampsia — biological predispositions (such as an elevated number of disease-associated alleles) may play roles.

Clayton Yates, professor of biology and director of Tuskegee University’s Center for Biomedical Research, studies the biological mechanisms responsible for the increased mortality rate of prostate cancer in black men.

“If we’re not understanding the disparities and the different mechanisms that are occurring at a biochemical level in different populations, it’s no wonder that a large percent of our drugs that get to market are failing in a general population,” he said, “because we’re not even considering that in the discovery process.”

In 2017, Yates and his colleagues received a five-year of nearly $8.5 million to help train minority scientists involved in health disparities research. The grant is one of seven that the NIMHD announced last year for research centers in minority institutions, or RCMIs, in Alabama, Florida, Tennessee, North Carolina, Arizona, Puerto Rico and Hawaii. The NIMHD plans to disburse $122 million over five years for the institutions to train early-career investigators involved in health disparities and minority health research and to improve research infrastructure.

A breast cancer cell, photographed by a scanning electron microscope. The disparity between breast cancer survival rates in black and white women has widened in recent years, despite decreases for both groups.COURTESY OF BRUCE WETZEL AND HARRY SCHAEFER, NATIONAL CANCER INSTITUTE, NATIONAL INSTITUTES OF HEALTH

A breast cancer cell, photographed by a scanning electron microscope. The disparity between breast cancer survival rates in black and white women has widened in recent years, despite decreases for both groups.COURTESY OF BRUCE WETZEL AND HARRY SCHAEFER, NATIONAL CANCER INSTITUTE, NATIONAL INSTITUTES OF HEALTH

In addition, last year the NIMHD announced it would direct over five years to 12 Centers of Excellence focused on multidisciplinary research and community-engagement activities.

Together, these grants made up around 15 percent of the NIMHD’s $281 million budget for 2017.

In addition to advocating for the elimination of policies that give rise to social inequality, health disparities experts say basic researchers can help address health disparities by questioning the established canon of biomedical research, building interdisciplinary collaborations, training scientists from underrepresented communities and enhancing community involvement through participatory research.

New frameworks for questions

How does inequity affect people at the molecular level? And how do those effects influence, for example, the rate of colorectal cancer in black men in Chicago? These are the types of questions being asked by researchers at the Chicago Center for Health Equity Research, or CHER.

There, Robert Winn and are part of a multidisciplinary from the University of Illinois at Chicago aiming to minimize disparities by examining the effects that continual violence and harassment have on the health of minority populations. The center, which is led jointly by Winn; Martha Daviglus, a cardiovascular researcher focused on health disparities; and Jesus Ramirez-Valles, a chair of the Division of Community Health Sciences at the university’s School of Public Health, was established last year after the university received a $6.75 million five-year grant from the NIMHD to develop a center of excellence on minority health and health disparities.

At the University of Illinois Cancer Center, Karriem Watson has helped create community-based programs for screening, preventiing and navigating breast, colorectal, cervical, prostate and lung cancer. COURTESY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT CHICAGO

At the University of Illinois Cancer Center, Karriem Watson has helped create community-based programs for screening, preventiing and navigating breast, colorectal, cervical, prostate and lung cancer. COURTESY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT CHICAGO

“We want to strengthen health-equity scholars and produce research activities that can expand the understanding of structural inequality in order to identify the differential risks and vulnerabilities of racial, ethnic, and sexual minority groups,” said Watson, who is also director of community engaged research and implementation science at the university’s cancer center.

The team has three projects that investigate health and structural violence. One examines the factors associated with disparities in mental health among Asian immigrant populations. Another examines the relationship between cardiovascular disease outcomes in Latino families and stress due to racial discrimination. The third examines colorectal cancer and the epigenetic impacts that structural violence has on black populations in Chicago.

“When you think of colorectal disparities on the south side of Chicago, you think about that as an issue that spans translational research,” said Winn, who is also the associate vice chancellor for community-based practice at the university. “That issue starts at the cellular-molecular level, with the actual testing and the understanding that biologists have of the pathology of colorectal cancer and diagnosis of colorectal cancer, all the way to the community uptake of that screening.”

The colorectal cancer project employs a mouse model that the researchers established with the help of , an associate professor specializing in animal models of gastroenterology. They can use the model to simulate food insecurity and stressful situations perpetuated by aspects of structural violence, such as social isolation, stress and trauma.

“We can mimic those situations in animal models to demonstrate how certain biochemical markers, such as cortisol, may be elevated in those animals and that may also be elevated in our human population,” which may illustrate environmentally induced epigenetic changes that cause an elevated risk of colorectal cancer, Winn said.

“That’s just an example, to me, of where we now have tools that we didn’t have (before) to study these really big issues of our society that actually do have a component that needs to be answered at the bench to be able to make any inroads,” Winn said.

In addition to his role at Chicago Center for Health Equity Research, Robert Winn is the primary investigator in a lab at the University of Illinois at Chicago that explores signaling pathways in lung cancer.COURTESY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT CHICAGO

In addition to his role at Chicago Center for Health Equity Research, Robert Winn is the primary investigator in a lab at the University of Illinois at Chicago that explores signaling pathways in lung cancer.COURTESY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT CHICAGO

Disparities in cancer

While health disparities are primarily a consequence of economic inequity and unequal access to health care, certain types of cancers — prostate cancer in black men and triple-negative breast cancer in black women are two examples — are believed to occur disproportionately due to higher frequencies of predisposed alleles.

At City of Hope Cancer Center in Duarte, California, Rick Kittles is exploring the link between ancestry-informative genetic markers and disease risk and outcomes, with a special emphasis on prostate cancer.

“The bulk of health disparities really doesn’t have any strong sort of biological component to it, it’s more social, cultural, behavioral differences across populations that are contributing to disparities,” said Kittles, the founding director of the Division of Health Equities at City of Hope. “But, there’s a subset — for instance, prostate cancer — which has a strong genetic component to it that might account for some of the differences that we see when we compare black men and white men and Hispanic men.”

While the overall death rates for cancer in black men and women have fallen by more than 34 and 19 percent, respectively, , they are still higher than the rates for the white population. Black men in the United States still have the lifetime probability of dying from prostate cancer as white men.

“We’ve identified across all populations a region on chromosome 8 that increases risk (for prostate cancer),” Kittles said. “The interesting thing is that the frequency of these risk alleles, these risk variants, are much greater in African-descent populations. When we do the math, because of the higher frequency, they can account for the higher frequency we see in prostate cancer in African-descent populations.”

The next generation

At the University of Hawaii at Manoa, Dean Jerris Hedges, Noreen Mokuau, Marla Berry and their colleagues are mentoring new and early-stage scientists to investigate health disparities in native Hawaiian and Filipino communities on the islands.

“We feel that if we can improve the health in those who have a gap in their overall lifespan and general wellness, then we can raise the health of all of the population,” said Hedges. “We’ve been doing this in a translational manner, trying to do bench-to-bedside-to-community (work).”

Altered lipid metabolism, shown in yellow, may be a key signature of prostate cancer.COURTESY OF JI-XIN CHENG, PURDUE UNIVERSITY CENTER FOR CANCER RESEARCH, NATIONAL CANCER INSTITUTE

Altered lipid metabolism, shown in yellow, may be a key signature of prostate cancer.COURTESY OF JI-XIN CHENG, PURDUE UNIVERSITY CENTER FOR CANCER RESEARCH, NATIONAL CANCER INSTITUTE

team received an RCMI grant from the NIMHD for nearly $5 million in to facilitate research on the causes of and most effective interventions for health disparities on the islands related to diabetes, cancer, glucose metabolism, cardiovascular disease and strokes. “There are elements of the current grant that focus not only on community, behavioral and public health aspects, but also are looking at the epigenetics that may affect certain populations to a greater extent than others,” Hedges said.

Part of the program focuses on introducing young scientists to experts in adjacent fields.

“(Each young investigator) has a partner or a collaborator or a mentor, or both, from a different discipline,” Berry said. These pairings tend to include basic research scientists partnered with clinical or community-based researchers or cross-disciplinary pairings such as biologists and engineers.

At Tuskegee University’s Center for Biomedical Research, Yates is using the NIMHD to train minority biomedical scientists who are examining disparities in HIV, obesity and prostate cancer.

Prior to his current role at the University of Hawaii at Manoa, Jerris Hedges served as professor and department chair in emergency medicine at Oregon Health & Science University’s School of Medicine.COURTESY OF TINA SHELTON

Prior to his current role at the University of Hawaii at Manoa, Jerris Hedges served as professor and department chair in emergency medicine at Oregon Health & Science University’s School of Medicine.COURTESY OF TINA SHELTON

“This grant has been a culmination of over 10 years of work through multiple other discoveries and papers, where we’ve identified that there are molecular and genetic differences, particularly in cell-signaling pathways that are associated with an aggressive (prostate cancer) tumor in an African-American patient versus a European-descended patient,” Yates said.

The funding will allow Yates and colleagues to expand the center’s research capacity by developing new laboratories and furnishing them with cutting-edge equipment. The program will operate adjacently with the center’s pre-existing National Cancer Institute-funded mentoring programs.

Tuskegee’s program pairs senior health disparities experts with new faculty members. The mentorship helps prepare the young investigators to answer disparities questions in their careers, Yates said.

They’re asking these questions, he said: “How do you address this population? How do you transform what you are currently doing to address a specific population that you see has a disproportionate outcome or incidence of disease?”

Lovell Jones is a retired molecular endocrinologist who has received numerous awards for his leadership in minority health disparities, including the ͵ĹÄ͵żú and ͵ĹÄ͵żú Biology’s Ruth Kirchstein Diversity in Science Award. Jones said he believes that these types of interdisciplinary partnerships are key to ensuring that the progress made in the laboratory ultimately has an effect outside of it.

Rick Kittles has been researching ancestry-informative genetic markers and how they can be utilizes in genomic studies on disease risk and outcomes for more than 20 years.COURTESY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO

Rick Kittles has been researching ancestry-informative genetic markers and how they can be utilizes in genomic studies on disease risk and outcomes for more than 20 years.COURTESY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO

“It’s not that (basic researchers) have to become experts in psychology or experts in sociology, experts in urban planning, but they need to have an array of colleagues that can advise them in terms of direction,” said Jones. “What has been asked before? What hasn’t been asked before? What has it done?”

These partnerships are particularly important at the University of Hawaii, where the nearest major academic institution is more than 2,500 miles away, Berry said. “The university plays a unique role in training local scientists to address health disparities within their own communities,” she said, “which makes developing these junior investigators particularly crucial.”

Community-based research

Helping train minority scientists to study disparities in their own communities is an approach that Kittles and his colleagues at City of Hope also favor.

“One of the goals, obviously, is to increase not only disparities research but also diversity among the researchers,” Kittles said. “For the most part, scientists study themselves, and so the more scientists of color we have, the more questions and opportunities to really explore this issue of disparity in the scientific community.”

In Belcourt, North Dakota, Native American geneticist Krystal Tsosie is working simultaneously as a co-investigator for a study involving genetic determinants of pregnancy-related high blood pressure, or pre-eclampsia, in the Turtle Mountain band of and wrapping up her Ph.D. in genomics and health disparities at Vanderbilt University.

“I find that people within these interdisciplinary fields tend to come from their communities of interest, so researchers have their own firsthand experience with what it’s like to grow up in these diverse, underrepresented communities,” Tsosie said. “Being a Native American scientist, particularly a Native American geneticist, you have to wear many hats, and, because there are so few of us, our expertise gets called upon collectively and individually at earlier stages in our training than maybe other traditional students.”

At Vanderbilt University, Krystal Tsosie used the BioVU database to longitudinally examine whether genetic determinants contributed to black women’s risk of developing uterine fibroids.COURTESY OF Vanderbilt University

At Vanderbilt University, Krystal Tsosie used the BioVU database to longitudinally examine whether genetic determinants contributed to black women’s risk of developing uterine fibroids.COURTESY OF Vanderbilt University

Prior to her work in Belcourt, Tsosie was using Vanderbilt’s database of more than 225,000 de-identified genetic samples to study genetic determinants of uterine fibroids in black women.

The pre-eclampsia project at Turtle Mountain Community College involves a research cohort of local residents who have been working with the institution for more than 15 years.

Pre-eclampsia occurs in about 6 percent of pregnancies and can result in premature birth and death for either, or both, the mother and child. Tsosie’s co-investigator, , is a family practitioner who has worked with the Indian Health Service in the Belcourt area since 1977.

While no genetic determinants have been found yet for pre-eclampsia, risk factors including mutations in DNA . By incorporating clinical data from electronic health records at the Belcourt-area Indian Health Service clinic, the researchers are able to examine potential environmental and sociocultural factors specific to women of the Turtle Mountain Chippewa Nation that may affect pre-eclampsia rates.

“In studies of diverse populations, Native Americans in the U.S. are very much ignored,” Tsosie said. “Part of it is, the population is so small to begin with. Another challenge is having an informed process that not only educates American Indians about the potential benefits of engaging in genomics research, but then having the cultural competency of researchers to engage a community to have more equitable research.”

Tsosie and colleagues have had a variety of research questions about the tribes’ saliva and blood samples and have kept tribe members abreast of the results that come from their samples through newsletters or radio programs. Additionally, they train tribal students in the lab and work with a Tribal Institutional Review Board, which reviews and approves their projects.

One project funded by the University of Hawaii’s NIMHD grant is an aquaponics pilot project at the WaimĂŁnalo Learning Center to promote healthy diets.COURTESY OF DEBORAH MANOG

One project funded by the University of Hawaii’s NIMHD grant is an aquaponics pilot project at the WaimĂŁnalo Learning Center to promote healthy diets.COURTESY OF DEBORAH MANOG

This community-based participatory research, which involves community engagement at every step of the scientific process, is how most of the genomics research within Native American communities has trended since a 2004 lawsuit in which the , in a remote part of the Grand Canyon, sued the Arizona Board of Regents and researchers at Arizona State University for misusing their DNA samples.

Lovell Jones is the founding co-chair of the Intercultural Cancer Council, the nation’s largest multicultural health policy group focused on minorities.COURTESY OF LOVELL JONES

Lovell Jones is the founding co-chair of the Intercultural Cancer Council, the nation’s largest multicultural health policy group focused on minorities.COURTESY OF LOVELL JONES

“We’re really hoping that encouraging community-engaged research, in not just Native American communities but in all diverse ethnic populations, as a broad agenda, will not only change how researchers interact with potential participants but also make research more equitable for all diverse and nondiverse populations,” Tsosie said.

At Tuskegee University, Yates and colleagues are involved in outreach programs led by campus investigators in venues such as town hall forums, where the researchers can tell community members about the elevated risk for prostate and breast cancers and how best to communicate that information with their doctors. The researchers partner with the Southern Christian Leadership network, a long-established presence in the community, to help disseminate this information and hold conferences across the state.

It can make a difference, for example, if community members know that tumors may be more aggressive in certain populations. “(That affects) how they have that conversation with the physician (and) how they stay on top of the clinical management and care of their own cancer tumors,” Yates said.

‘A national concern’

As the demographic makeup of the country changes each year, disparities affect a larger percent of the population, which both the health care system and the researchers who make treatments possible need to reckon with.

In 2017, the NIMHD’s annual budget came in 22nd out of the NIH’s 27 institutes and centers at $281 million, making up less than 1 percent of the NIH’s total for the year. At $33.1 billion, the NIH’s budget is just 3 percent of the federal government’s for discretionary spending.

Jones, who was the founding director of the Health Disparities, Education, Awareness, Research and Training Consortium, is bullish on addressing health disparities on a societal level.

“Yes, the stock market is going up. Yes, unemployment rates are going down. But how long is that going to last when the population of your nation becomes less healthy as the demographics change and you do not address this population with these demographic health issues?” Jones said. “Ten, 20 years ago, it was a community concern. It was a population concern. But today it’s a national concern.”

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition weekly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Guiding grocery carts to shape healthy habits

Robert “Nate” Helsley will receive the Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator in Lipid Research Award at the 2025 ASBMB Annual Meeting, April 12–15 in Chicago.

Quantifying how proteins in microbe and host interact

“To develop better vaccines, we need new methods and a better understanding of the antibody responses that develop in immune individuals,” author Johan Malmström said.

Leading the charge for gender equity

Nicole Woitowich will receive the ASBMB Emerging Leadership Award at the 2025 ASBMB Annual meeting, April 12–15 in Chicago.

CRISPR gene editing: Moving closer to home

With the first medical therapy approved, there’s a lot going on in the genome editing field, including the discovery of CRISPR-like DNA-snippers called Fanzors in an odd menagerie of eukaryotic critters.

Finding a missing piece for neurodegenerative disease research

Ursula Jakob and a team at the University of Michigan have found that the molecule polyphosphate could be what scientists call the “mystery density” inside fibrils associated with Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and related conditions.

From the journals: JLR

Enzymes as a therapeutic target for liver disease. Role of AMPK in chronic liver disease Zebrafish as a model for retinal dysfunction. Read about the recent JLR papers on these topics.