Focus on exposure

In past columns, I’ve made the point that figure preparation begins at data acquisition, but I haven’t really explained my reasoning in depth. So here, I’ll fill you in. Once you’ve snapped your picture or exposed your Western blot, that image becomes the version of record for your experiment. If the data you’ve collected is poor quality from the outset, your figure is already compromised.

One way to tell if you’ve nailed your image’s acquisition parameters is to look at your image’s histogram. Being able to interpret the histogram correctly can tell you if you can move forward with snapping the next picture of your mutant phenotype or if you need to tinker with the acquisition settings.

If you’re a digital photography aficionado, you probably are very familiar with histograms and the information they contain. Here’s a quick overview for those not yet accustomed to viewing them: A histogram of an image displays the distribution of pixels in the image, showing a graph of the number of pixels with a given intensity. For an eight-bit grayscale image, there are 256 possible intensities ranging from 0 (black) to 255 (white) for each pixel in the image. The histogram will not tell you how these pixels are distributed in space, just the distribution of the pixel intensity.

Ideally, you want the pixels to lie between the two extremes. This ensures that the fine details of your images are captured. If the pixels are clustered at either end, you’ve likely oversaturated or underexposed your image. For example, aggressively adjusting the black levels of an immunofluorescence image to reduce the background eliminates hallmarks of a true experimental image. On the other hand, oversaturation leads to loss of fine details and makes it impossible to quantify the signal. Why? From the point of view of the detector, i.e., the camera or film, once it has recorded the maximum amount of signal, it cannot register any more. If you’ve hit the limit on either end of the histogram, the detector won’t be able to tell you if a band or a cell feature is two times or 20 times more intense than a neighboring band or cell.

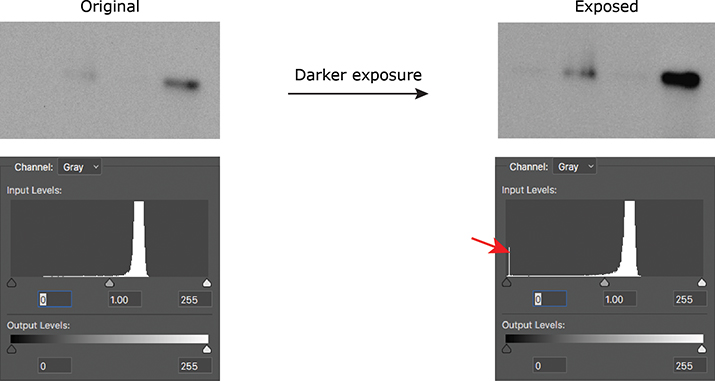

If you’re acquiring images on a microscope or gel-documentation system, the hard part already is done for you, because these instruments typically show you the histogram of the image you’ve just acquired. If you are using film, take multiple exposures of your blot to make sure you are within the linear range of the signal so you can properly quantify it. Once you’ve scanned your film, you can use either Photoshop or ImageJ to look at the histogram of your image. A telltale blip at either end of the histogram will tell you that you need to adjust your acquisition settings or use a different exposure of your film (Figure 1).

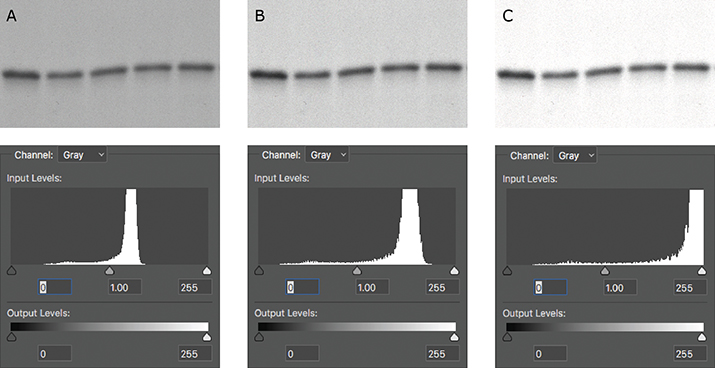

The histogram is also useful in telling you if your image has been overadjusted during figure preparation. After you’ve adjusted the brightness or contrast settings of your image, make sure to check the histogram one final time. If the histogram has shifted too far to the left or to the right, you’ve likely truncated the pixels that were at the ends of the distribution, and your image is now overly adjusted (Figure 2). If your histogram shifts too far to either end, the resulting image may raise flags with reviewers or the journal, because it may look like you’re trying to hide something. Remember, there’s no need to hide your true experimental results!

Doing your due diligence at the image-acquisition phase will save you time as you prepare your figures for publication, which could be months or even years after you initially acquired your data. Going back and repeating an experiment because an immunofluorescent image was underexposed or a band was completely blown out can be frustrating, to say the least, so use these tips to make the most out of your data.

Figure 1. A spike on the histogram at 0 (red arrow) indicates that a Western blot was burned out (all black); a spike at 255 would have indicated that the blot was overexposed (all white).

Figure 1. A spike on the histogram at 0 (red arrow) indicates that a Western blot was burned out (all black); a spike at 255 would have indicated that the blot was overexposed (all white). Figure 2. (A) The original capture of an immunoblot (B) Some of the levels were adjusted, but the pixels were still distributed between the two extremes. (C) The immunoblot was overly adjusted. The corresponding histogram shifted to the right, indicating that the majority of the pixels now were white.

Figure 2. (A) The original capture of an immunoblot (B) Some of the levels were adjusted, but the pixels were still distributed between the two extremes. (C) The immunoblot was overly adjusted. The corresponding histogram shifted to the right, indicating that the majority of the pixels now were white.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition weekly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and weтАЩll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Transforming learning through innovation and collaboration

Neena Grover will receive the William C. Rose Award for Exemplary Contributions to Education at the 2025 ASBMB Annual Meeting, April 12тАУ15 in Chicago.

Guiding grocery carts to shape healthy habits

Robert тАЬNateтАЭ Helsley will receive the Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator in Lipid Research Award at the 2025 ASBMB Annual Meeting, April 12тАУ15 in Chicago.

Quantifying how proteins in microbe and host interact

тАЬTo develop better vaccines, we need new methods and a better understanding of the antibody responses that develop in immune individuals,тАЭ author Johan Malmström said.

Leading the charge for gender equity

Nicole Woitowich will receive the ASBMB Emerging Leadership Award at the 2025 ASBMB Annual meeting, April 12тАУ15 in Chicago.

CRISPR gene editing: Moving closer to home

With the first medical therapy approved, thereтАЩs a lot going on in the genome editing field, including the discovery of CRISPR-like DNA-snippers called Fanzors in an odd menagerie of eukaryotic critters.

Finding a missing piece for neurodegenerative disease research

Ursula Jakob and a team at the University of Michigan have found that the molecule polyphosphate could be what scientists call the тАЬmystery densityтАЭ inside fibrils associated with AlzheimerтАЩs, ParkinsonтАЩs and related conditions.