JBC: Snug as a bug in the mud

Lipids are ubiquitous molecules, serving as structural building blocks for membranes, messengers in cell signaling or compounds for energy storage. Their versatility relies in part on the presence of one or more double bonds in the long lipid carbon chains. The more double bonds a lipid has, the more unsaturated it is; and the more unsaturated lipids there are in a membrane, the more flexible the membrane tends to be.

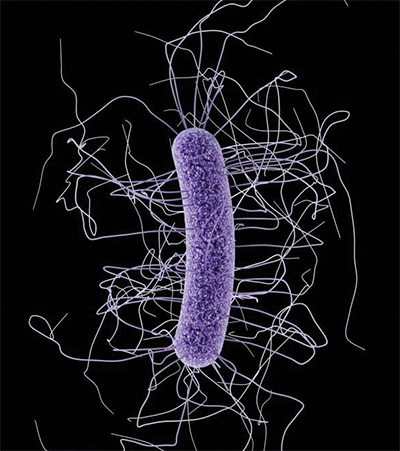

Anaerobic bacteria such as clostridia (Clostridium difficile is shown here) can produce unsaturated long-chain fatty acids in the absence of molecular oxygen.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Anaerobic bacteria such as clostridia (Clostridium difficile is shown here) can produce unsaturated long-chain fatty acids in the absence of molecular oxygen.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

To make unsaturated fatty acids, cells growing in the presence of molecular oxygen have an advantage; they can use this powerful oxidant to insert a double bond into a fatty acid chain via a dehydrogenation reaction. But what about organisms that cannot grow in the presence of molecular oxygen?

This question piqued the curiosity of Harvard professor , who had a long-standing interest in oxygen as a biosynthetic reagent and knew that molecular oxygen is toxic to some microorganisms. During a summer course in the 1950s taught by the eminent microbiologist Cornelius van Niel, Bloch became acquainted with obligately anaerobic bacteria that thrive only in the absence of oxygen.

, an emeritus professor of microbiology at the University of Pennsylvania, worked with Bloch on bacterial fatty acid biosynthesis. He said Van Niel’s course caused Bloch “to wonder what goes on in anaerobes, because obviously, they couldn’t use molecular oxygen.”

To answer this, Bloch studied fatty acid biosynthesis in two species of the anaerobic bacteria clostridia.

Konrad Bloch“Clostridia are present anywhere where there’s no oxygen,” Goldfine said. “If you look in mud several inches below the surface, you’ll find clostridia, and they’re happily growing.”

Konrad Bloch“Clostridia are present anywhere where there’s no oxygen,” Goldfine said. “If you look in mud several inches below the surface, you’ll find clostridia, and they’re happily growing.”

In 1961, Bloch, Goldfine and colleagues published two papers in the Journal of Biological Chemistry on unsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis in clostridia. The papers, now recognized as JBC Classics, reported that the clostridia species produce unsaturated fatty acids via a route distinct from that in aerobic cells.

Goldfine’s association with Bloch began through their shared interest in anaerobic metabolism. Goldfine was working on anaerobic bacteria in Earl Stadtman’s lab at the National Heart Institute of the National Institutes of Health.

“(Bloch) was coming down to NIH for a study section, and he asked if we could have lunch together, and then he asked, would I be interested in coming to visit his lab?” Goldfine said.

Goldfine knew Bloch’s work on cholesterol and fatty acids, for which Bloch was to win the Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine with Feodor Lynen in 1964. Goldfine jumped at the opportunity and stayed for three years in the Bloch lab.

“I was really very, very fortunate to have had the opportunity to work with Bloch, because he was a man of really great depth and understanding,” Goldfine said. “It was a turning point in my career.”

Goldfine’s expertise soon was tested: Removing all oxygen from the experimental system to study unsaturated fatty acids in anaerobic organisms posed a challenge. He first tried to grow the clostridia in a helium atmosphere in a vacuum desiccator, “but that didn’t completely remove oxygen, because there could be a trace of oxygen in the helium,” he said.

So Goldfine resorted to a chemical trick and skillful lab acrobatics. He poured a 5% potassium carbonate solution into the desiccator base, above which he placed the flasks holding the bacteria along with a beaker containing pyrogallic acid. After sealing the desiccator, Goldfine gingerly tilted it to tip the pyrogallol into the potassium carbonate solution. The resulting mixture removed any traces of oxygen from the helium-filled desiccator.

Howard GoldfineThe researchers relied on Bloch’s expertise in radiocarbon labeling and detection. After feeding 14C-labeled lipid precursor acetate to the bacterial cultures, Bloch and Goldfine extracted the lipids from the cells, used gas chromatography to separate fatty acids, identified them with standards and assessed them for 14C labeling in a scintillation counter.

Howard GoldfineThe researchers relied on Bloch’s expertise in radiocarbon labeling and detection. After feeding 14C-labeled lipid precursor acetate to the bacterial cultures, Bloch and Goldfine extracted the lipids from the cells, used gas chromatography to separate fatty acids, identified them with standards and assessed them for 14C labeling in a scintillation counter.

In the , Goldfine and Bloch reported incorporation of two-thirds of the 14C-labeled acetate into saturated lipids and one-third into monounsaturated lipids, showing that bacteria can produce unsaturated fatty acids in the absence of molecular oxygen.

But how could the anaerobic clostridia create double bonds in fatty acids?

To answer this question, Goldfine and Bloch fed a series of 14C-labeled saturated fatty acids ranging in length from 8 to 18 carbons to the cells. They found that the clostridia do not make unsaturated fatty acids by desaturating bonds in their saturated counterparts. Instead, the clostridia produce a single double bond during elongation of the short (8–10 carbons long) saturated fatty acids, resulting in long-chain monounsaturated fatty acids.

Bloch and colleagues then noticed that the unsaturated fatty acids differed in where the double bond was located in the lipid chain, resulting in different fatty acid isomers.

To find out how these isomers were made, as described in the , Bloch, Goldfine and another member of the lab, , fed 14C-labeled octanoic and decanoic acids to a clostridium and again measured 14C incorporation into fatty acids. They tweaked their procedure to include exposure to a strong oxidant that breaks lipid double bonds, enabling them to home in on the mechanism that creates the different fatty acid isomers.

“I distinctly remember Paul Baronowsky — he was a graduate student at the time — standing at the blackboard at the end of the lab writing that pathway,” Goldfine said. “‘This is how you get the double bond here. And if you do it with another precursor, you get the double bond there.’ He drew it all out beautifully.”

Their experiments clearly showed that the individual isomers don’t arise from interconversions among them and established which short-chain fatty acids are the precursors to the various long-chain fatty acid isomers.

Thus, innovative rejiggering of lab equipment, foundational biochemistry methods and several incisive blackboard sketches helped uncover how anaerobes make unsaturated fatty acids.

The results of Bloch’s lab stood the test of time. “The pathway that is in the second JBC (Classics) paper has held up for 60 years,” Goldfine said. “It’s pretty astonishing.”

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition weekly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and weŌĆÖll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Guiding grocery carts to shape healthy habits

Robert ŌĆ£NateŌĆØ Helsley will receive the Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator in Lipid Research Award at the 2025 ASBMB Annual Meeting, April 12ŌĆō15 in Chicago.

Quantifying how proteins in microbe and host interact

ŌĆ£To develop better vaccines, we need new methods and a better understanding of the antibody responses that develop in immune individuals,ŌĆØ author Johan Malmström said.

Leading the charge for gender equity

Nicole Woitowich will receive the ASBMB Emerging Leadership Award at the 2025 ASBMB Annual meeting, April 12ŌĆō15 in Chicago.

CRISPR gene editing: Moving closer to home

With the first medical therapy approved, thereŌĆÖs a lot going on in the genome editing field, including the discovery of CRISPR-like DNA-snippers called Fanzors in an odd menagerie of eukaryotic critters.

Finding a missing piece for neurodegenerative disease research

Ursula Jakob and a team at the University of Michigan have found that the molecule polyphosphate could be what scientists call the ŌĆ£mystery densityŌĆØ inside fibrils associated with AlzheimerŌĆÖs, ParkinsonŌĆÖs and related conditions.

From the journals: JLR

Enzymes as a therapeutic target for liver disease. Role of AMPK in chronic liver disease Zebrafish as a model for retinal dysfunction. Read about the recent JLR papers on these topics.