JBC: A focus on iron

Proverbs like “an apple a day keeps the doctor away” remind us that certain foods promote good health. However, it may be less apparent that metals are an essential part of our diet. Miniscule amounts of numerous metals are present in an apple — iron, sodium, potassium, calcium and magnesium — all of which are necessary for life. “Metals in Biology,” a thematic review series started in 2009 in the Journal of Biological Chemistry, takes a closer look at diverse metals and their roles.

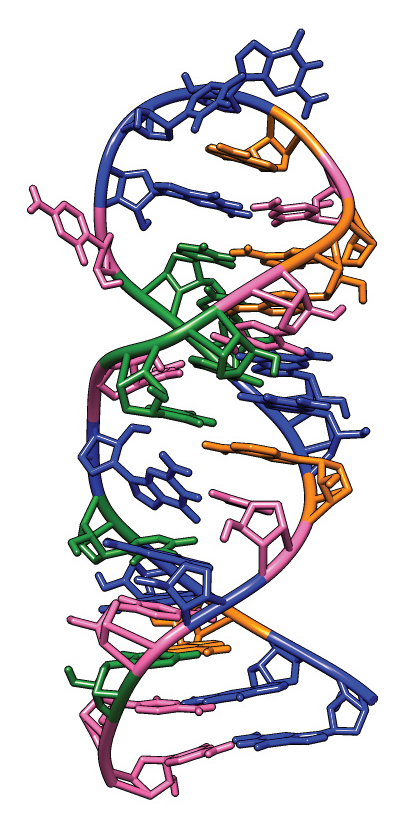

This image shows the main components of the structure of the 30-nucleotide iron-responsive element located near the 5’ end of the messenger RNA of ferritin.Courtesy of Nunziata Maio/Journal of biological chemistry The six minireviews in the of the series provide new insights into why iron is “the king of metals in biology,” according to of Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, the JBC deputy editor who coordinates the series. “Iron is relatively abundant in the human body and has a great variety of roles,” Guengerich said, “including electron transfer, structural contributions and a role in iron-sulfur clusters (iron in complex with either a cysteine or sulfide linkage). Although magnesium and zinc are also abundant and important, as far as we know they do not undergo redox chemistry,” which limits their versatility.

This image shows the main components of the structure of the 30-nucleotide iron-responsive element located near the 5’ end of the messenger RNA of ferritin.Courtesy of Nunziata Maio/Journal of biological chemistry The six minireviews in the of the series provide new insights into why iron is “the king of metals in biology,” according to of Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, the JBC deputy editor who coordinates the series. “Iron is relatively abundant in the human body and has a great variety of roles,” Guengerich said, “including electron transfer, structural contributions and a role in iron-sulfur clusters (iron in complex with either a cysteine or sulfide linkage). Although magnesium and zinc are also abundant and important, as far as we know they do not undergo redox chemistry,” which limits their versatility.

The first two reviews in the series, by Richard Coffey, Tomas Ganz and Mitchell D. Knutson, give an overview of how iron is acquired, used and stored in the body, including the cell types and molecular pathways involved. Mammals have adapted to holding onto their iron because no regulated excretion exists. However, too much iron is toxic, so it is regulated primarily at the level of nutritional iron absorption in our gut and the tightly controlled release of iron from its main storage in the liver into circulation in the body. Interestingly, the membrane transporter involved in iron uptake in the gut, called divalent metal-ion transporter 1, or DMT1, was also the first mammalian transmembrane iron transporter to be discovered 20 years ago, igniting the iron biology field. Taken together, these first two reviews introduce the reader to major insights into iron biology from the past two decades.

The third review, by Tracey Rouault and Nunziate Maio, takes a closer look at how iron levels are sensed and regulated in the body.

Early insights in this area arose from studies of ferritin, a major iron-storage protein, which is translationally regulated by iron regulatory protein 1, or IRP1, and its iron–sulfur cluster switch. When cellular iron is low, IRP1 lacks the iron–sulfur cluster and binds ferritin’s mRNA to decrease its translation and, ultimately, iron storage. This same IRP1 switch can increase the translation of other iron regulators that in turn increase iron absorption in the gut and import more iron into cells. Many other proteins besides IRP1 contain iron–sulfur clusters; the best known examples are mitochondrial proteins involved in oxidative phosphorylation, known as Complex I and II, where these clusters are used as electron carriers. However, questions remain pertaining to their synthesis in cells and their delivery to appropriate proteins. The third review discusses the progression of this field and concludes that “it is possible that hundreds of Fe-S proteins are present in mammalian cells, waiting to be identified.” Therefore, many new insights in this field are to be expected. The fourth review, by Joseph Braymer and Roland Lill, goes into mechanistic aspects of iron–sulfur cluster syntheses in mitochondria to further elaborate this process.

Iron ions, either free or bound in heme groups or iron–sulfur clusters, must be transported in the cell by specialized proteins called chaperones. For example, the dietary iron that is taken up by the gut cells via the iron importer DMT1 must be transported by an iron chaperone from the importer to the exporter ferroportin before it can be shuttled by transferrin throughout the body. The fifth review, by Caroline Philpott and colleagues, offers insight into how iron transport in cells is mediated by iron metal chaperones.

The last review of this series, by Sharleen V. Menezes and colleagues, looks at the importance of iron in cancer metastasis.

Specifically, it focuses on the regulation of Nmyc downstream-regulated gene 1, or NDRG1, which is a well-known metastasis suppressor associated with favorable prognosis in several cancer types. However, “the roles of iron in cancer are complex,” Guengerich said. “Also, dysregulation of iron metabolism can increase tumor growth, and cancer cells can exhibit an enhanced dependence on iron, a phenomenon termed ‘iron addiction.’” This review is only a small part of the picture, and controversies exist in this area.

Iron has been featured in most installments of “Metals in Biology.” This is the second time it is the sole focus. Other metals will be included in the future. “I do not think we will cover every metal in the periodic chart, in that some are not very relevant in biology,” Guengerich said. “We will try to highlight work with the most relevant metals but also provide some insight to some which have less frequent occurrences in biology, as we have in the past (e.g., nickel and vanadium).”

The next installment will focus on copper. “Copper has many of the same properties of its transition metal colleague iron,” Guengerich said, “but it is not as ubiquitous in terms of roles and the number of enzymes. As in the case of iron, free copper is deleterious, and the homeostasis is tightly controlled by a number of biological mechanisms.”

And while that daily apple has some health benefits, the iron in apples is not the most bio-available form for humans. If your body needs more iron, animal products (such as red meats, fish and poultry) are a better source of so-called heme-bound iron, which can be absorbed by your body much more efficiently.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition weekly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Guiding grocery carts to shape healthy habits

Robert “Nate” Helsley will receive the Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator in Lipid Research Award at the 2025 ASBMB Annual Meeting, April 12–15 in Chicago.

Quantifying how proteins in microbe and host interact

“To develop better vaccines, we need new methods and a better understanding of the antibody responses that develop in immune individuals,” author Johan Malmström said.

Leading the charge for gender equity

Nicole Woitowich will receive the ASBMB Emerging Leadership Award at the 2025 ASBMB Annual meeting, April 12–15 in Chicago.

CRISPR gene editing: Moving closer to home

With the first medical therapy approved, there’s a lot going on in the genome editing field, including the discovery of CRISPR-like DNA-snippers called Fanzors in an odd menagerie of eukaryotic critters.

Finding a missing piece for neurodegenerative disease research

Ursula Jakob and a team at the University of Michigan have found that the molecule polyphosphate could be what scientists call the “mystery density” inside fibrils associated with Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and related conditions.

From the journals: JLR

Enzymes as a therapeutic target for liver disease. Role of AMPK in chronic liver disease Zebrafish as a model for retinal dysfunction. Read about the recent JLR papers on these topics.